We were approaching the end of our time in India and to be honest, we were all ready to go. We were close to our 6th week in India and although Kochi was a welcome change in scenery from Rajasthan, we couldn’t wait to move on to our next country. Our Airbnb in Kochi was so comfortable and with the convenience of food and grocery delivery, the kids were not motivated to leave the house. The tropical climate, heat and humidity, made it even less appealing to go outside. I’ll admit that it wasn’t just the kids. I also felt tempted to hole up at home. But, after a good night’s sleep, I just couldn’t let the opportunity to see Kochi slip away. Much to my kids’ dismay, I booked a walking tour of Old Kochi.

When I first contacted Siyad, he told me that he had some medical issues that he needed to take care of so wouldn’t be available for the next few days. I told him our timing was flexible and wished him good health. He messaged back and suggested that he might be available, but that he was preparing for a trip and hoped to get some rest. I wasn’t sure what he was trying to tell me. After a few back and forth messages, Sayid offered a date and time to show us around Old Kochi.

I was half-expecting a sickly old man to show up. I couldn’t have been more off the mark. Sayid, youthful and energetic, picked us up on the edge of Old Kochi in his own tuktuk. I wouldn’t have been more pleased than if he showed up in a Ferrari. It was a convenience and a luxury for our guide to have his own transportation that could seat, barely, us all. Sayid was a jovial man, his demeaner accentuated by his salt and pepper beard, with a warm disposition. He was born and has lived in Kochi his entire life. He told us straight away that Kerala was different from the rest of India. The reason that he seemed the proudest of was the religious diversity and tolerance. Muslims face discrimination all over India, but here, Hindus, Muslims and Christians lived and worked side-by-side in the same neighborhoods and communities. Sayid himself, a Muslim, was proud of the fact that he has had both Hindu and Christian friends since childhood. The rise of the Narendra Modi and his BJP Party in the past ten years had done nothing to change that.

At some point along the tour, Sayid revealed to us some details about the medical issues he needed to take care of and the trip that he was about to take. Fortunately, he wasn’t in poor health. He just needed to get his annual medical evaluation before he embarked on a trip leading handicapped travelers on a 2-week tour through India. Our first reaction was one of awe. Even tourists who are fully able-bodied struggle with mobility in India. We certainly struggled to weave through narrow and crowded lanes, cross streets with ferocious oncoming traffic and navigate deteriorating inclines and stairs in old palaces and forts. Sayid admitted that it was indeed difficult and exhausting, but it was incredibly fulfilling work. Visiting India is the life-long dream of some of these travelers and without him, they would never be able to do it. After we learned this about Sayid, we admired and respected him in a whole different way.

A proper tour of Old Kochi could not possibly skip over a stop at the famous Chinese fishing nets. Today, there were five fishermen operating one of the fishing nets. The nets require at least four fishermen to operate the cantilever with a massive net on one side and a counterweight of various stones dangling from ropes on the other. The contraption looked really complicated but with the old fishermen, operating it was like a choreographed dance they had performed countless times. The fishermen saw us watching them and motioned for us to walk onto the plank and join them. Although I was curious and I wanted to, we demurred because we didn’t want to get caught in an awkward situation regarding how much to tip them. We watched for a bit longer and saw them pull up the net they had just released into the water a few minutes before. It was not a bountiful catch. There were just a few fish floundering around in the net. They collected their measly catch and submerged the net back into the water again.

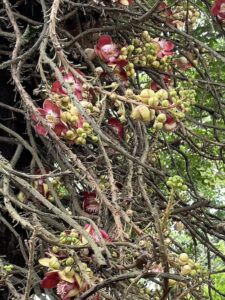

We hopped onto Sayid’s tuktuk and stopped on an unassuming street. Kochi is covered with rich vegetation. Trees and plants seem to grow everywhere. Spontaneously and automatically, life seems to find a way to poke out of the rich tropical soil anywhere that isn’t covered in concrete but they even find a way through narrow cracks in the pavement. Sayid pointed to a tree that was covered with beautiful magenta flowers. The flowers looked like hundreds of mangosteens peeled open and hanging from the tree. Many of the flowers hadn’t blossomed and were still in their pods. The most interesting part of this tree was not the flowers or the pods. This is the Canonball tree and it gets its name because its fruit, in size and shape, resembles a cannonball. Although beautiful, this tree is among a number of invasive species in Kochi that is threatening its native flora. Sayid knows because it was his friend who planted the first tree of this species in Kochi, from a seed he brought back from South America.

We made a quick stop at the Koder House. The Koder House is now a heritage hotel but it was originally a Portuguese mansion built in the early 19th century. In the early 20th century, the mansion was purchased by Samuel Koder, the head of a promient Jewish Family in Kochi, and converted to their family home for several generations. The Koders and their descendants were deeply involved in the thriving Jewish community of Kochi in the early- and mid-1900s. At its peak, the Jewish community reached a population of 2,000 people. Today, there are only a few, probably less than five elderly Jews, who continue to live in Kochi.

The history of the Jews in Kochi is a fascinating one. They are believed to have arrived in Kerala over 2,000 years ago as sailors on King Solomon’s boats. They were welcomed by the then Hindu ruler, King Sri Parkaran Iravi, and settled in a port city about 30 miles north of Kochi. For thousands of years, the Jews lived in close proximity to Hindus, Muslims and Christians and are said not to have faced racial or religious discrimination by the majority population. This is another testament to Kerala’s success as a multi-racial, multi-religious community.

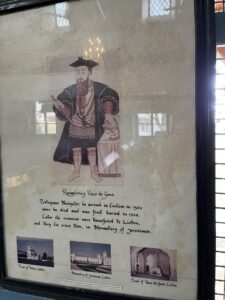

We stopped at the St. Francis Church that has a beautiful white façade that looks recently restored. Constructed in 1503 by Portuguese Francisco Friars, it is believed to be one of the first Christian church built in India by Europeans. Its original construction was of wood and mud. The church’s other claim to fame is that it was the original tomb of Vasco de Gama, a Portuguese explorer who was the first to reach India by sea. Vasco de Gama died in 1524 during his third visit to India. After his death, he was buried in St. Francis Church. Fourteen years later, his remains were returned to Portugal.

The stamp of the Dutch East India Company could be easily spotted in the architecture of the city. We walked passed the VOC Gate. “VOC” stands for “Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie”, which means United East India Company in Dutch. The gate was built in 1740 when the Dutch East India Company was the richest and most successful private company in the world. Behind the gate were administrative buildings of the VOC. This was not the first time we had encountered the VOC stamp. We had seen the extent of the Dutch East India Company’s reach throughout the Western Cape of South Africa.

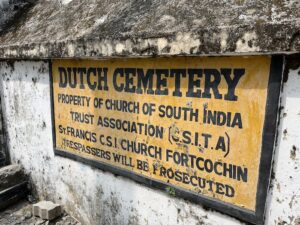

After the Dutch East India Company defeated the Portuguese in the 17th century and Kochi came under Dutch control, the church was converted to a Dutch Reformation Church. The Dutch cemetery that was constructed in 1724 next to the church, still stands there today.

Sayid is a lover of nature, especially trees. Every few steps, he stopped to point something out to us growing along the road. He had taken us to see the Canonball tree and now he wanted to show us his favorite tree in all of Kochi. He stopped his tuktuk at the side of the road and pointed to the magnificent Banyan tree.

Our next stop was the fascinating Dhoby Khana public laundry. The first thing we saw when we entered the building were rows of shirtless men wearing the Tamil lungi engrossed in ironing work. There was also a friendly woman dressed in a sari using a charcoal iron to press men’s work shirts. With modern washers and dryers available at such an affordable price, it was shocking that Dhoby Khana still exists. Most of the men and women working inside could only be described as elderly. They had gray or white hair and looked like they had been working in the laundry for most of their lives.

The history of the Dhoby Khana extends all the way back to colonial times when the Dutch, in the 1720s, recruited members of the Tamil Nadu and Malabar communities to work in Fort Kochi to wash Dutch uniforms. At that time, the laundry was located in the ponds at Veli, with the community allocated 13 acres of land and each family given a pond to do the washing. In 1976, the government constructed Dhoby Khana for the community as compensation for 10 acres of the original land that the Tamils “sold” to the government.

We walked through Dhoby Khana and watched the laundrymen and women doing their work. Many of the workers smiled and welcomed us to their workplace. Sayid told us that each family had been allocated a space for washing, drying and ironing. The ownership transfers to children and descendents. Men and women were manually doing the back-breaking work of washing clothes by hand. They soaked the clothing in huge tubs of water and detergent and then twisted, wrung and beat the laundry onto huge stones to make them clean.

All of the washed clothing were hang-dried under the hot sun creating a picturesque scene of fresh-washed clothing billowing in the wind. It is up to each family to get customers and most of the business comes from small hotels and individuals. Hanging on the long drying lines were sheets, pillowcases and colorful clothing of all sizes and styles. The last step of the process, which we saw earlier, was the ironing.

We stopped to chat with an old lady who was doing her washing. She was petit with white hair and looked to be at least 80 years old. Sayid seemed to know her and the two were engaged in a conversation. Sayid stopped to translate bits of the conversation, telling us that she had been having a tough time with her health. Her feet, especially, were bothering her. While doing the washing, the workers stand almost knee-deep in cold water for half the day. It seemed inevitable that this would cause health problems. She went on to say that her son and daughter were not intersted in working in laundry, so she had no choice but to continue. The kids couldn’t believe that this old lady was around the same age as their grandparents and worked in these conditions. Indeed, it is hard to believe, but we who are a little longer in the tooth know that these are harsh realities that exist all over the world. Sayid handed her some bills that he had wadded up in his pocket and she thanked him. She smiled to us and waved goodbye as we left. On our way out, we found a donation box and stuffed in some money that we hoped would help in some way.

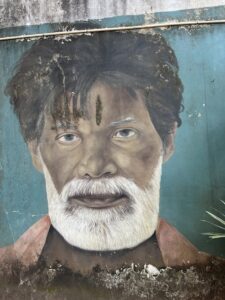

On our way in, we had passed by a mural, a portrait, of a man’s face painted on the wall. The mural was as tall as I was. I stood in front of the painting and looked again, lingering on the man’s eyes. Was it an expression of tiredness? Resignation? Determination? Peace? I couldn’t tell. Sayid saw me looking at the portrait that was painted several years ago for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. Sayid pointed in the direction of the laundry and told me that the subject of the portrait was the man working in the laundry. He had been ironing the clothes at the front. I immediately recognized him and remembered who he was talking about. The man was shirtless, engrossed in his ironing, and since the portrait, had colored his hair with henna. I looked it up later and found that the Kochi Biennale is the biggest art exhibition in India and the biggest contemporary art festival in Asia.

The afternoon sun was making it oppressively hot and humid. We had to stop for a break. Sayid brought us to a local shop selling fresh coconuts.

We weren’t feeling any cooler after the coconuts, but at least we weren’t thirsty anymore. We hopped onto Sayid’s tuktuk and headed for Jew Town. The name, Jew Town, sounded strange to us, potentially construed as offensive to Jews, but it is actually the accepted name for the Jewish district of Kochi and a source of pride for the residents and their descendants as a sign of Jewish identity and autonomy in the community.

Under Dutch rule, the Jews enjoyed civil and religions liberties. Along with the growth of the spice trade, the mercantile Jewish community thrived and became a highly respected minority in Kochi. Under British rule, the Jews continued to flourish and during their peak in the mid-20th century, there were around 2,000 Jews and eight synagogues in Kochi. After India gained its independence in 1947 and post-World War 2 when Israel was formed, many of the Cochin Jews emigrated to Israel.

We headed for Paradesi Synagogue, the only operating synagogue remaining in Kochi. Because there are only a handful of Jews that continue to live in Kochi, service is only conducted when there are ten male members present to complete a minyan, or a quorum of ten.

Paradesi Synangogue was constructed in 1568 on land gifted to the Jewish community by the then King of Cochin. It was destroyed by the Portuguese in 1662 and reconstructed a few years later under Dutch rule.

We removed our shoes before entering the synagogue and despite the oppressive heat made worse by the stillness inside, we noticed the beauty surrounding us. The synagogue was filled with crystal chandeliers, imported from Belgian, and colored lanters that cast a soft glow throughout the room. A single hanging chandeliers would have been beautiful, but the sheer number of chandeliers, each one different, hanging in the room made it a mesmerizing sight.

Glancing down at the floor, we immediately noticed the eye-catching blue-and-white floor tiles that looked somewhat out of place. These floor tiles were hand-painted in Canton, China in the blue and white pattern that was popular during the time. Because each tile was hand-painted, there are no two tiles that are identical.

The kids were growing impatient in the humidity but we had one more stop to go. Sayid took us in his tuktuk to the largest spice trader in Kochi. We expected to see a Costco-sized modern warehouse stacked with sealed boxes and bags of pungent spices ready for export. But the place we entered bore no resemblence to a Costco. It was just a medium sized room with open sacks of all varieties of spices including cardamom, black cardamom, black pepper, cinnamon, cumin, mace, tumeric, black pepper and many more. In the room next door was a medium sized storeroom with more bags of spices waiting to be sold. By observing this modest operation, it was hard to believe that this was one of the largest spice and most professional spice traders in Kochi that has been run the same family for generations since the 18th century when Kochi was under Dutch rule. The kids were getting impatient and I knew that I was out of time to find the answers my questions. We said goodbye to Sayid and wished him good luck on his upcoming tour.

We were preparing to leave Kochi the next day and in knowing that are remaining days in India were limited, we felt compelled to indulge in our last few local meals. Leo had been wanting to try a traditional Malayalam sadya meal served on banana leaf. The kids were not interested so we left them at home to enjoy some Chinese delivery and free-time. Leo and I snuck off for a lunch date.

When we got back, we told the kids about our meal and showed them pictures. They said it looked spicy, but it piqued their interest. On our 37th and last day in India, we went to another restaurant that served sadya as well as other a la carte items. Knowing this would be our last day and last meal in India, we ordered curries, seafood, fish and breads and ate with abandon.

Author

-

Song is the mother of four children. She and her family have stepped away from it all and in September 2023, began traveling the world while homeschooling. Song is an ABC (American born Chinese) and has an undergraduate degree from Cornell and an MBA from Harvard. She is an entrepreneur and an educator. Her hobbies include learning, traveling, reading, cooking and baking, and being with children.