It’s hard to believe, but Chandni Chowk was even more crowded than it looked. One of the oldest and busiest marketplaces in Old Delhi, Chandni Chowk was a constant barrage of sounds, sights and smells. Everything screamed for attention –from shiny gold bangles and vibrant saris to colorful ribbons and shiny tassels and even cheap Santa suits and plastic Christmas decorations dangling from shop stalls that lined the narrow alleys. Different kinds of delicious smells wafted from food stalls into the streets and nested in the fabric, hair and even skin of the passers-by. Vendors hawked their wares, music blared, people shoved, horns honked and everybody talked at increasing volumes just so they could be heard.

We’ve been to some pretty crowded places in China before (flashback to Guangzhou Zoo during Chinese New Year in 2015, Chengdu Panda Sanctuary in the summer of 2022). In Chinese, we say 人山人海(people mountain, people sea) when a place is crowded, but Chandni Chowk was an a whole different level.

Did I ever mention that I hate crowds? Wherever we go, I assiduously try to avoid crowds. Of course, when given a choice, probably few people would choose the unpleasant discomfort of crowds. But beyond the physical, there is also the idea of the totally arbitrary and unnecessary competition for resources that gets to me. I hate squeezing with hundreds or thousands of other people to enjoy a venue or visit a sight during peak times when the same place would be empty during off-peak times. My disdain for crowds is one of the many reasons that convinced us to travel this year. There are no schedules or holidays (school, public or work) to dictate when we can go somewhere. We have all the autonomy to choose when to go and at any given time, somewhere in the world, it is low season.

But I get the feeling that Chandni Chowk without the crowds is not Chandni Chowk. Rajesh said exactly that. When he hasn’t been to Chandni Chowk for a while, he actually misses the atmosphere. We tried our best to keep our group of 16 intact and also avoid being trampled while soaking up this once-in-a-lifetime experience. Without Rajesh, I don’t think we would be able to navigate the maze of narrow streets. Those who suffer from claustrophobia would almost certainly have issues in some parts of Chandni Chowk. I’m sure it is possible to get lost for hours with seemingly no way out.

We emerged from the narrow streets and stopped at a famous stall for jalebi (deep-fried fermented batter soaked in sugar syrup). Rajesh said there were a few famous jalebi shops in the market, but this was the best one. Indeed, there was a long line and there was a big sign on the stall that read “We have no other branch”. The jalebi, like many Indian desserts was extremely sweet. It was fresh and tasty and everybody liked it.

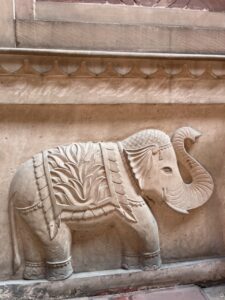

Despite what it seemed, we weren’t walking aimlessly. We had a destination – a lunch booking at Haveli Dharampura. During Shah Jahan’s reign during the Mughal dynasty, what is now known as Old Delhi was called Shahjahanabad. Shah Jahan moved the Mughal capital from Agra to Shahjahanabad in 1648. Shahjahanabad was once the site of many beautiful havelis (mansions) that were home to the city’s wealthy politicians and merchants. After the fall of the Mughal dynasty, the havelis lay in neglect and eventually in total disrepair. To this day, many of the once magnificent havelis in Old Delhi are crumbling and in desperate need of repair and restoration. Haveli Dharampura is one of the rare exceptions.

Built in 1887 during the late Mughal and colonial period, Havelia Dharampura was in a state of disrepair when it was discovered by Vijay Goel and his son. The passionate father and son team spent six years to return the old haveli to its former glory. With the help of local historians, professional architects and skilled craftsmen, the haveli has been restored as close as possible to its original design and appearance. With its intricate carvings, open-air balconies and roof-top views over Old Delhi all the way to Jama Masjid, it was presented with an award from UNESCO for heritage and conservation.

After pressing our way shoulder-to-shoulder through the narrow lanes of the market, then wondering if the tangled web of wires and cables above us were a fire hazard, our group walked into the old haveli and it felt like we had entered into another world. Nobody could have guessed that a charming and peaceful panacea of calm existed in the middle of the craziness of Chandni Chowk.

The entrance of the haveli is discrete. The only clues that there is something special inside are the extra high steps leading to the entrance and the intricate floral carvings on the red sandstone façade. We walked through the light-filled courtyard where the sound of water could be heard coming from the delicate water fountain in the center of the inlaid marble floor. A long table had been set for us in the dining room that opened to the central courtyard through picturesque Mughal doorways with scalloped and cusped arches.

Before lunch would be served, we were invited upstairs to the rooftop. We climbed several flights of stairs, each more narrow and steep than the previous, until we reached the final spiral staircase painted a vibrant turquoise color, that led us to the highest point in the haveli. There was a kite master flying a kite high above the skies of Old Delhi.

The children were each presented with their own paper kite. For our skill level, the platform was too small for more than one kite to be flying at once so we all focused our energy on the original kite that was already suspended in the air. Keeping the kite bobbing up and up appeared to be so easy when we were just watching. The master kitesman let us each have a turn handling the kite that seemed safely suspended in the clouds. The kids seemed to be pretty good at it, but when it came to my turn, I realized that it wasn’t as easy as it looked. As if someone had attached an invisible weight to it, I watched helplessly as the kite took a downward dive.

As we looked across the skyline of this old and crowded part of town, we saw the unmistakable demands of everyday life. On rooftops as far as the eye could see, there were rusty water tanks and laundry flapping about in the wind. Above the hustle and bustle of life below, we also got a glimpse of dreams. On rooftops across Old Delhi, there were lots of others flying kites too. Our master kitesman said there would be a kite festival in a few weeks’ time and many of the children were practicing for the festival.

It was time for lunch, so we headed back downstairs to indulge in a truly sumptuous feast. One course after another was served. At the end of it all, we all could have used an afternoon nap. But we didn’t have time for that. We still had more of Old Delhi to see.

We really didn’t want to brave through the entire Chandni Chowk again, but we didn’t have a choice. We worked our way backwards, past the web of electric wires, past the narrow alleys full of vendors selling lace, tassels and ribbons, past the shops glittering with gold bangles, past the colorful sari stalls, past the stalls selling street food and out onto the main street.

Too tired to walk any further, Rajesh found us some rickshaws and we rode in style to the old spice market. Khari Baoli, Asia’s largest wholesale spice market, was established in the 17th century by the Mughals. Some of the shops in the market have been run by the same families since that time, now into the 9th or 10th generation.

Tumeric, coriander, mustard seeds, cloves cardamom, mace, black peppercorn, fenugreek and many more are spices commonly used in Indian cooking. The variety of spices used in Indian cooking is overwhelming. I have always shied away from cooking Indian food from scratch because understanding and acquiring the spices is simply too daunting. Chinese cooking feels simple by comparison. A bottle of soy sauce, some salt and sugar, sometimes vinegar and you are good to go. But of course, to my Indian friends, the spices used in Indian cooking are no big deal.

The main business for most of the shops in the spice market are wholesale, but some are also quite attuned to what tourists want. Some shops sold pre-mixed spice packets for favorite Indian dishes like chicken tikka masala, butter chicken, palak paneer, etc.

By the time we were done at the spice market, it was almost 6 pm and the sky was nearly dark. We got onto some rickshaws and headed back to our tour bus. It seemed that lots of other people had the same idea because the road out of the spice market was bumper to bumper, or for rickshaws, wheel to wheel.

It was dinnertime, but we were all still full from lunch. As a compromise between dinner and no dinner, Rajesh suggested we stop by one of his favorite street food stalls serving Qureshi kebab. He described it as being better than tandoori chicken because it is tender, flavorful and falls off the skewer. How could we refuse?

It took the bus far longer than we expected to reach the Qureshi stall, but we were getting used to that. There were a few guys working in the stall and we watched one of them squish the Qureshi paste in between their fingers to form a sausage shape that he then pushed onto metal skewers. Qureshi is made of minced chicken meat paste, so smooth that it doesn’t even resemble meat, marinated in spices and then grilled over charcoal for a smokey flavor. To go along with the meat, we ordered some butter naan. The guy making the naan had a little cushion that he stretched the naan over and used it to adhere the dough to the inside wall of a tandoor clay oven. That’s how he gets the naan thin and chewy.

There were a few young kids who came by the stall begging for money or food. Their clothes were dirty, hair unkempt and they had no shoes. Who knows where their parents were. As sad as it is, this is not an unusual sight in New Delhi. It probably has something to do with poverty, but it’s not just that. A few months ago, we were in Kenya where the per capita GDP is slightly less than India, USD 2200 compared to India’s USD 2500. Despite being a poorer country, begging in Kenya was uncommon. In New Delhi, beggars seemed to be everywhere.

The children approached us and tugged at our sleeves and grabbed onto our arms. Every time they came, the workers from the kebab stall would yell at them and chase them away. It seemed like a game to both sides. The kids were not afraid and always came back giggling. The men were not angry, actually they seemed to be playing with the children. After a few times of the back and forth, one of the men grabbed a stick and raised it above his head, pretending like he would strike the kids. He didn’t really look angry, but I couldn’t predict what might happen next or later.

It is always difficult to know whether to give to beggars. It is even harder to know whether to give to child beggars. Like most people, I feel torn. Everybody deserves to live with dignity and all children deserve to have a comfortable home, enough food, clean water and parents who love them. But of course, that isn’t how the world is.

I looked online to find some information about begging in India. Begging is perfectly legal in many places, including Delhi. With the absence of a central law banning begging, it is up to each state and jurisdiction to create their own laws on begging. In fact, begging in California is also legal, protected under the First Amendment of free speech, but if beggars become aggressive or threatening, it becomes panhandling which is illegal.

Beyond the obvious reasons for begging like poverty and unemployment, begging is so common in Delhi because according to netizens, beggars can actually earn pretty good money. Sometimes, they can earn more than in a menial job. Some beggars, fully capable of finding a job opt for begging instead. Those who see begging as an endeavor of choice, not necessity, may no longer feel shame or desire to advance in society. Begging then becomes a business. Beggars could be working in an organized ring with a boss, like in the movie Slumdog Millionaire, sometimes exploiting children or vulnerable individuals in cruel ways. The world is never transparent. It’s impossible to know who is begging by choice, who is begging by necessity and who is being exploited or coerced.

Should we help beggars then? It is a question that I continue to wrestle with, without getting any closer to an answer. Like most people, I naturally feel more sympathy to children and those with physical disabilities or deformities. In a twist a fate, if my children were born into unfortunate circumstances, I hope they would be lucky enough to meet the kindness of strangers.

Some people have created rules to help us know how to behave. Some tell us to ignore all beggars. We should never give to beggars because it only perpetuates the problem. Some advise us never give to beggars that look able-bodied but we should give food to children. Some say we should give exclusively to handicapped or deformed beggars.

I’m probably like most people. I give if I am particularly moved or if I happen to have spare change in my pocket. It is often a matter of chance or circumstance, what is happening at that moment, what I notice or how I feel that determines what I do. I find that I have a much greater inclination to give money to individuals who are doing something, anything more than just begging, to earn the money. Throughout our travels, we have spoken to our kids extensively on this topic and I admit there is no best or even good answer. Everybody must decide for themselves how to deal with beggars. In India, there is no avoiding the subject.

When we arrived back at the hotel, we all gathered in our room to try the qureshi kebabs. The first thing we noticed was that the meat was an unnatural orange color. Color aside, it was tender and fragrant but we all preferred the traditional tandoori kebabs with whole pieces of meat. It was late and memories of the day were swirling around in my mind. We all needed to get to sleep because tomorrow would be another long day and I already knew that everything we encountered would demand attention.

Author

-

Song is the mother of four children. She and her family have stepped away from it all and in September 2023, began traveling the world while homeschooling. Song is an ABC (American born Chinese) and has an undergraduate degree from Cornell and an MBA from Harvard. She is an entrepreneur and an educator. Her hobbies include learning, traveling, reading, cooking and baking, and being with children.